Microservices and monoliths: getting service-oriented architectures just right

In my previous post about software architecture I introduced a methodology for creating architecture for new software projects that aims to encapsulate areas of volatility in discrete services.

Note: If you are unfamiliar with what “areas of volatility” means in the context of software architecture, I would highly recommend reading my previous post about software architecture before reading the rest of this article

Going through this process is pretty straightforward for brand new projects, but who has the luxury of working on brand new projects all the time? Not most software developers!

The majority of software developers are primarily maintaining or adding features to existing software systems, but if you ask a group of software developers if they’d rather work on a brand new project or maintain an existing system, the response will overwhelmingly favor working on new projects. In fact, desire to work with newer technologies or on new projects is one of the more common reasons people cite for leaving a job. Why do you think this is?

Identifying problems is easy; fixing them is hard

When you maintain an existing system, it’s easy to identify problems with its architecture. Why? Because good architecture results in a system that’s easy to change.

When you’re asked to change an existing system that wasn’t designed to encapsulate volatility, the weakness of the design becomes self-evident. Even the smallest surface-level changes can send ripples of complexity throughout the rest of the system: new dependencies perpetuate seemingly endlessly, already bloated method signatures gain even more parameters, automated tests explode in size and complexity while reducing in actual utility.

Do these problems sound familiar?

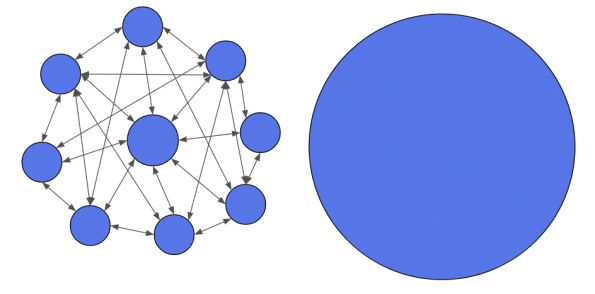

Does your architecture look like this?

If so, you have a monolith.

The monolith is easily the most common architecture, or lack thereof, seen in the kinds of existing systems most software developers work on.

The monolith emerges from systems that weren’t designed at all, or weren’t designed to encapsulate volatility, but have grown in size and complexity as business needs evolve over time.

So what do you do with a monolith?

Everybody feels the pain when working on a monolith, developers and business people alike. Developers hate working on monoliths because the difficulty of implementing new behavior grows with each new behavior added to the monolith. Once a monolith reaches critical mass, changing the behavior of a monolith becomes a truly terrifying proposition. Productivity drops, morale drops, and the business is impacted. Businesses want to move fast, and monoliths become slower over time. This is not a good place to be.

Where do we go from here?

Many developers will want to throw the whole thing out and start over, but this idea won’t fly with the business. You’ll hear something like this: The best software is the one that’s currently making you money, no matter how great the hypothetical new version is imagined to be!

So you need a new plan that doesn’t involve throwing out the monolith, but still allows you to move forward without further increasing the size of the already bloated monolith.

Microservices?

Microservices is a buzz word that vaguely conveys the idea of a service oriented architecture with multiple discrete services.

On the surface, microservices seem like the antithesis of the monolith (and everyone hates monoliths!), so many microservice architectures emerge from monoliths by taking new feature requests and implementing them as discrete services, and herein lies the problem: when your monolith already encapsulates all of your system’s volatility, breaking out new features into discrete services doesn’t save you from any of that volatility!

At first, it might seem like implementing new features as discrete services is helping things.

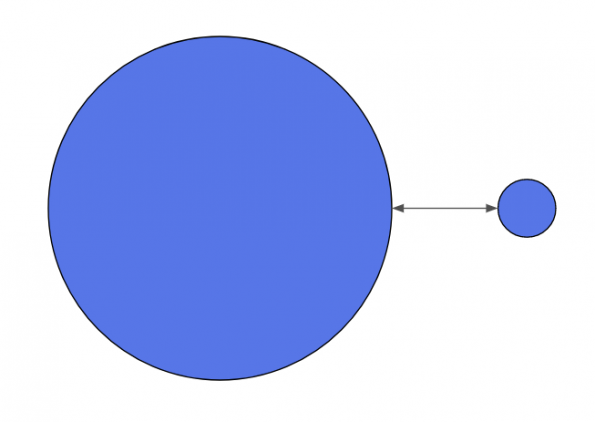

Here’s what a monolith with a single feature implemented as a microservice might look like

The monolith is a little bit smaller, and the new feature is cleanly decoupled from the rest of the system. This is good right?

What happens when the next feature request comes in?

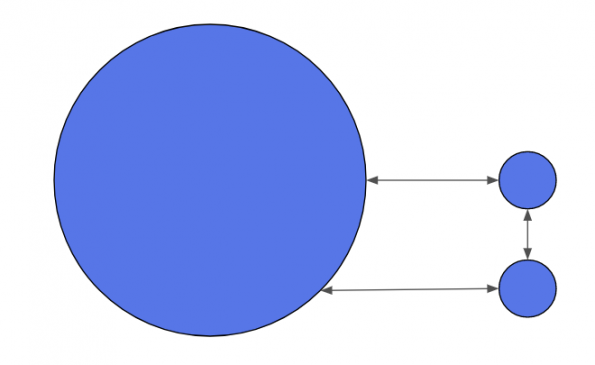

Uh oh. Two features in and we’re already seeing a problem. The second feature actually built on top of the first feature, so it can’t be completely isolated.

Let’s fast forward. Here is what you might end up with many features requests later if you simply carve out new microservices as feature requests come in without encapsulating complete areas of volatility

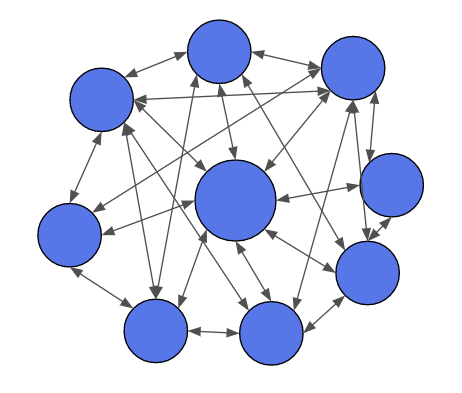

Did we improve things?

Let’s look at our microservices next to our original monolith

If you squint your eyes and let all those service dependency lines blur together, you’ll see the problem.

You’ve simply invented a more complicated monolith.

Small changes still send ripples of complexity throughout the entire system, they just do it differently now. Changing behavior of the system as a whole is going to now involve changing multiple microservices. All the same problems are emerging again, possibly even worse, exacerbated by the fact that the dependencies are harder to trace and carefully orchestrated multi-service deployments are even scarier than deploying a monolith.

What went wrong?

The problem stems from the fact that microservices alone isn’t architecture. Microservices is simply a word that vaguely describes systems that operate as discrete services rather than as a monolith. The actual practice of software architecture involves carefully planning where to draw the boundaries between discrete services. When you simply take a monolith and implement new behavior as discrete services, you aren’t going through the necessary planning to draw these boundaries meaningfully. Services bounded by features are essentially arbitrary.

You can’t do architecture without looking at the system as a whole

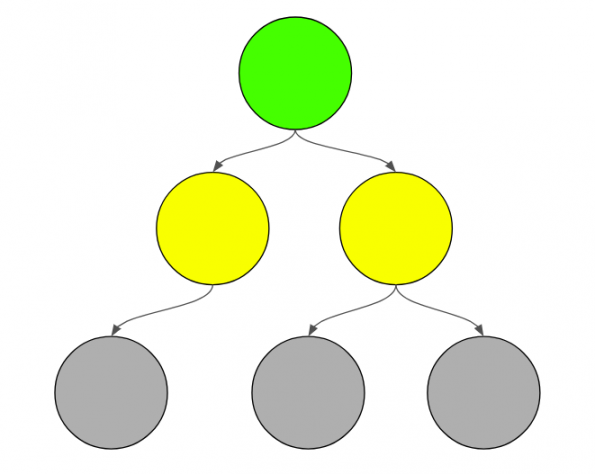

So if monoliths are too big, and feature-driven microservices are too small, how do we get to just right?

Know where you want to go

Go through the process of designing an ideal architecture for your system as a whole as if you were going to create it from scratch. Look at the system as a whole, and not just at new features. New feature requests being difficult may be the catalyst for launching a re-architecture effort, but that effort should consider the entire system in scope. This effort will result in giving you a clear picture of the finish line.

There are many ways to decompose a system, but I personally advocate for decomposing based on areas of volatility. This will result in just the right number of discrete services so that implementing new behavior in a system is as painless as possible.

You’ll wind up something that looks more like this

Actually implementing a new architecture is always going to be difficult, but at least now you have a specific goal in mind right from the start!

I’d love to give general advice for all software developers looking to implement new architecture to break apart an existing monolith, but the reality is that this road map is going to completely unique to each system. The important points to takeaway from this post are

- You can’t create good architecture if you only architect new features and ignore the existing monolith

- Monoliths can’t be effectively broken up without thinking about the system as a whole

- Microservices is just a buzz word. Smaller is not always better. Thoughtfully drawn service boundaries are what’s important

- You can draw just the right number of service boundaries by encapsulating areas of volatility

Pingback: tadalafil

Pingback: buy female viagra online canada

Pingback: cialis 30 day free trial

Pingback: sildenafil 50mg prices

Pingback: cialis online canada paypal

Pingback: apollo pharmacy online

Pingback: viagra 10mg price

Pingback: where can i get female viagra pills

Pingback: cialis before and after pictures

Pingback: valium pharmacy india

Pingback: what is super cialis

Pingback: 20 mg generic viagra

Pingback: buy viagra in australia

Pingback: best female viagra 2018

Pingback: cialis en espanol

Pingback: cost of cialis 5mg

Pingback: cialis generic 20 mg 30 pills

Pingback: metronidazole honey

Pingback: medications gabapentin-300mg

Pingback: tamoxifen dzialanie

Pingback: lyrica for spinal stenosis

Pingback: metformin ilaçlari

Pingback: indicaciones lasix

Pingback: penggunaan metronidazole

Pingback: keflex side effects elderly

Pingback: antenatal escitalopram use and necrotizing enterocolitis in a newborn: a case report

Pingback: how long does amoxicillin clavulanate stay in your system

Pingback: can you eat eggs while taking ciprofloxacin

Pingback: can i take cephalexin while pregnant

Pingback: diclofenac sodium 75 mg

Pingback: depakote alternatives

Pingback: amitriptyline side effects

Pingback: aripiprazole class

Pingback: celecoxib interactions

Pingback: celexa for depression

Pingback: protonix side effects mayo clinic

Pingback: acarbose mims

Pingback: effexor pregnancy category

Pingback: why take diltiazem on empty stomach

Pingback: ivermectin generic

Pingback: sitagliptin interactions

Pingback: side effects of voltaren

Pingback: robaxin side effect

Pingback: actos inmorales

Pingback: venlafaxine price without insurance

Pingback: remeron high blood pressure

Pingback: repaglinide properties

Pingback: spironolactone ef 40

Pingback: synthroid dosing

Pingback: tamsulosin blood pressure effect

Pingback: tadalafil contraindications

Pingback: sildenafil dosage

Pingback: buy levitra online usa

Pingback: ivermectin virus

Pingback: buy ivermectin pills

Pingback: viagra no prescription canada

Pingback: madison james research tadalafil reviews

Pingback: female viagra where to buy

Pingback: prednisone taper schedule

Pingback: where can i buy nolvadex online

Pingback: ciprofloxacin tooth infection

Pingback: is keflex good for tooth infection

Pingback: amoxicillin breastfeeding

Pingback: valacyclovir is used for what

Pingback: metronidazole for trichomoniasis

Pingback: lisinopril cough

Pingback: lyrica controlled substance